By Tsarizm Staff | November 8, 2020

If you don’t believe in ghosts, visit Spaç Prison—about an hour and 45 minutes north of Tirana. It’s impossible not to feel the pain of the many political prisoners who struggled and died here during Enver Hoxha’s 40-year Stalinist regime that is sometimes compared to current North Korea.

There were 60 prisons and internment camps during this time where 577 men and 450 women were executed and another 1,000 died—but Spaç was one of the most notorious. It opened in 1968 in a remote and mountainous area of northern Albania and remained in operation until the early 1990s.

Some of the most prominent intellectuals were sent here often on fabricated charges that deemed them enemies of the state, including French-born Albanian artist Maks Velo who was sentenced to 10 years in Spaç in 1978. He described the prison as “the most terrible camp in Europe, and I think in the world during this period.”

A local firsthand account

During one visit to Spaç, a local painter working on the exterior of the prison gave a firsthand account of growing up in a nearby village. Mario Gjeci explained that family members on his father’s side collectively spent 50 years here as prisoners. On his mother’s side, her family spent 10 years in harsh internment. His own brother-in-law did 12 years for trying to flee the country.

“Prisoners were subjected to long hours of working underground by hand in the copper mines in stifling heat that could reach 40˚C (104˚F), their lungs clogged by toxic dust and fumes,” he said. “Above ground, the temperature could drop to a frigid -10˚C (14˚F).”

Many died working with little food or clothing to protect them from the harsh working and living conditions. Their bodies unceremoniously thrown down the sides of the steep mountainside.

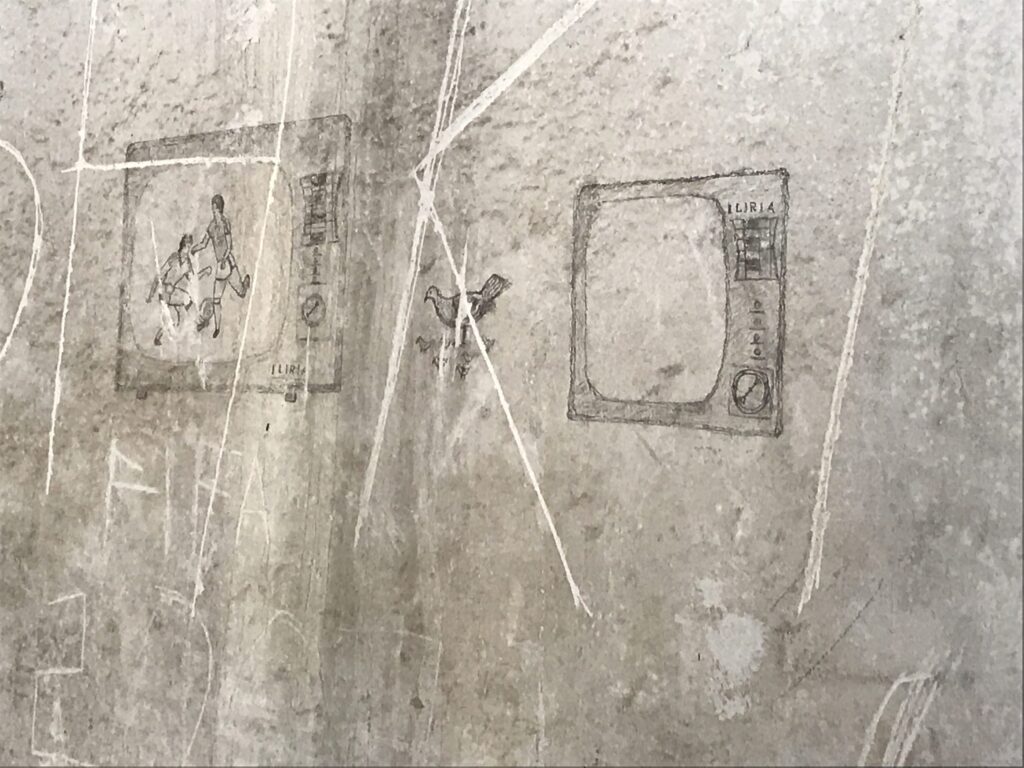

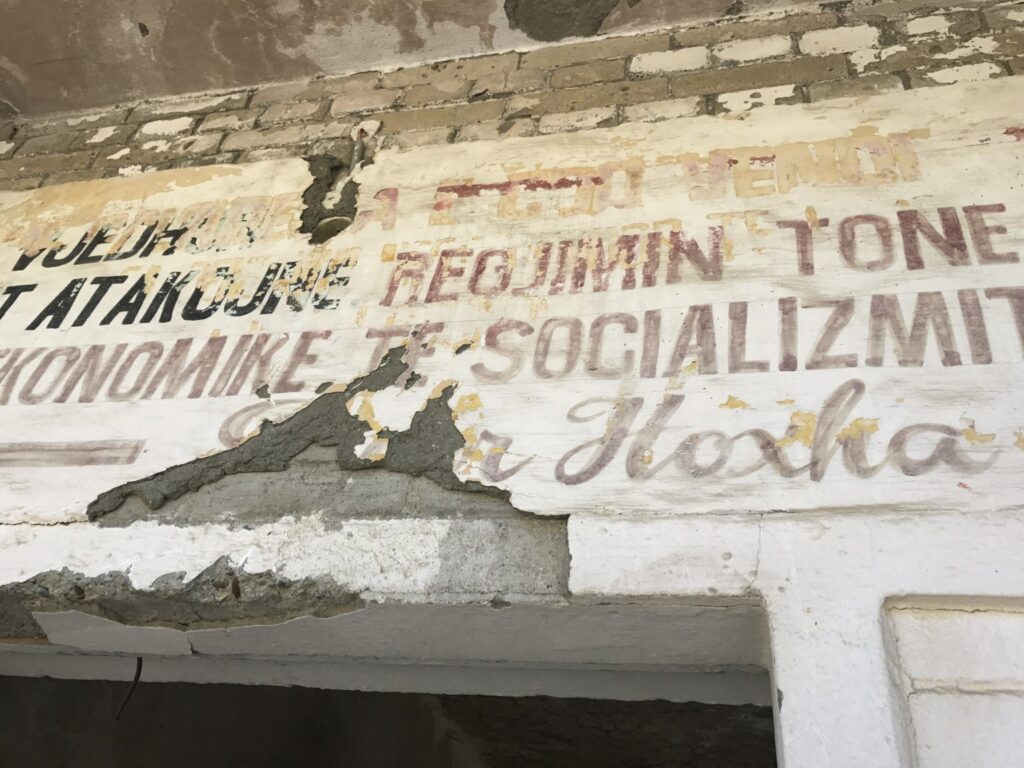

“Haunting drawings made by prisoners remain on the walls and ceilings in cells that once held 50 men to one room. A few faded Hoxha slogans can be seen above some of the prison doors,” Mario added.

The mountains surrounding Spaç were so severe, no perimeter wall was needed to keep prisoners from escaping.

“37 years ago, the state construction company brought us to work on a bridge over there. I could see the internment camp below with three rows of barbed wire with a search light covering every meter. The sentry posts were six meters high and roadblocks were every 50 meters,” Mario said. “At every roadblock, there were two sentries who were equipped with a machine gun, pistols, and army knives.”

In May 1973, there was a prisoners’ revolt, one of the first acts of resistance to Hoxha’s isolationist oppression. Prisoners took control of Spaç for two days and raised an Albanian flag without the communist star—a symbolic act they would pay a high price for. The revolt ended when the guards cut off food and water. Four leaders of the revolt were executed and 1,400 years of jail time were added to the terms of another 100 prisoners.

“Not even a fly could not escape,” Mario said. “I am astonished that even after 37 years, Europe and the rest of the free world doesn’t know about the existence of the Spaç internment camp. This is a gulag built by Albania. In his opinion, it was more dangerous than Auschwitz. Spaç is being lost in time and this is truly a crime—trying to hide the truth by letting the camp crumble.”

Spaç today, a rapidly deteriorating cultural site

Today, the abandoned complex is deteriorating rapidly due to exposure and looting by locals who have stripped metal from the doorways, fixtures from rooms and anything else that can be sold for scrap.

The New York-based World Monument Fund listed Spaç Prison as one of the 50 most endangered monuments in the world. The prison was also declared a second category national monument of culture by the Albanian government in December 2007. And the Swedish embassy in Tirana helped fund some site clearance, emergency roof repairs and temporary structural stabilization in 2017.

The Minister of Culture declared the protection of Spaç a priority, but little preservation has happened, And the buildings are in an extremely advanced state of deterioration.

The World Monuments Watch noted that there is no other site in Albania that currently serves as a place in Albania to honor the memory of former political prisoners. “There is a pressing need to advance knowledge, raise public awareness, and create a demand for the transformation of this site into a center of remembrance and education.”

Of the 17,900 Albanians who were imprisoned for 914,00 years during the Communist era, about 2,700 are still alive today. (Another 30,000 Albanians were sent to internment camps.)

And it is not just Mario who worries about the prison disappearing. Many of those who survived are concerned that their ordeals at Spaç will be forgotten forever as the prison turns to dust.

- How The Russian Revolution Brought The Father Of The Helicopter To America

- Poisoned Russian Opposition Leader Navalny Makes Weird Statement, Says US Election ‘Conducted Fairly’, Raising Questions As To Possible Globalist Ties In West

This piece originally appeared on Tsarizm.com and is used by permission.

The opinions expressed by contributors and/or content partners are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Steve Gruber.

Join the Discussion

COMMENTS POLICY: We have no tolerance for messages of violence, racism, vulgarity, obscenity or other such discourteous behavior. Thank you for contributing to a respectful and useful online dialogue.